Collecting Marine Life for Research

|

This digression will stray from the topic of how to build a high tech reef aquarium to that of how one stocks it once it is built. The obvious solution is to visit your local aquarium dealer and pick out exotic species shipped in from around the world. This is certainly the easiest thing to do, but you will of necessity pay a premium for your selections. This is because the livestock losses that the dealer will inevitably sustain to offer you the healthy samples on display, must be amortized over all items in order for the dealer to make a profit. If on the other hand you are willing to take on the risk of losses while buying a “pig in a poke,” you can have items transhipped directly to you from either volume dealers or from the source. You can potentially save a lot of money doing this, but you may get some unpleasant surprises when your shipment isn’t quite what you expected or it contains dead or dying livestock. A third option exists that can be very fulfilling, but for most of us it isn’t the kind of thing that we will exercise very often-- that is, to collect our own livestock. It is great to be able to point to a beautiful specimen thriving in your aquarium and be able to say that “I collected that myself!” Whether you scuba dive or simply snorkel, it is marvelous to have acres of specimens to choose from in the wild. Its free! And there is so much! You can be as picky as you want. You can also select those interesting things that never make it into your local aquarium store (for example, when is the last time you saw sand dollars in a store? I collected some at St. Petersburg, FL last year and they are still alive a year later, gently stirring my aragonite sand). I have been fortunate to travel for business-related activities to Hawaii and Florida. I was determined that while others were only talking about collecting their own livestock, I would do it. When these targets of opportunity arose, I found out how to legally obtain specimens and also planned ways to get them back to my tank alive. The balance of this article will discuss not so much how to physically collect things, but how to legally collect things. Both Hawaii and Florida are perhaps the most difficult states in which to collect marine life. Both states have heavily legislated the taking of certain corals (typically all reef-building corals) and ornamental fish. Consider first Hawaii. Good luck if you think you are going to sneak marine specimens out because you go through agricultural customs prior to flying out of the state. Florida on the other hand, though heavily regulated, has no such choke-points to check for contraband, so I am sure a lot of things are smuggled out both knowingly and unknowingly by visitors. Why take such chances when collecting can be done within the rules established? |

| Michelson at a favorite collection site. |

Hawaii

Consider first Hawaii. I surfed the world wide web long enough to get the phone number for the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources. They sent me an “Application for a Scientific Collecting Permit” which asks why you want to collect, what you want to collect, how you plan to collect them, who will be doing the collecting, and what will be done with the specimens.

Based on this application, I was issued an official “Permit to Engage in Certain Prohibited Activities in the Waters of the State of Hawaii.” The permit limited me to collection, by hand, of no more than 50 lbs of dead coral or reef rubble, with associated aquatic life. Specific locations were off limits. These were principally marine life conservation districts (MLCD). Those for the island of Oahu are shown below, but all other areas were open season.

The permit was very specific in its duration, April 28, 1997 through May 9, 1997, and within one month of the expiration of the permit, I had to submit the original permit to the Division of Aquatic Resources with a complete report describing all collecting done.

Finally, I was responsible for notifying the Division of Conservation and Resources Enforcement at least 48 hours in advance of any field collecting activity to provide such information as: location, date, time, and the number of persons to be involved. Though this may have been to check up on my activities, I was told that its real purpose was to keep enforcement officials from attempting to “bust” permitted collectors based on anonymous tips from locals who might observe the collection activity.

Of particular interest to reef collectors is Hawaii statute §188-68 entitled, “Stony coral; rock with marine life attached; taking and selling prohibited— which states that (a) The taking of any rock to which marine life is visibly attached or affixed, or live stony coral of the taxonomic order, Madreporaria, including the Fungidae or Pocilloporidae families, for any reason, is prohibited except with a permit authorized under section 187A-6 or section 183-41 or by the department under rules adopted pursuant to chapter 91 necessary for collecting marine life visibly attached to rocks placed in the water for a commercial purpose. (b) After July 1, 1992, no person shall sell or offer sale as souvenirs any stony coral of the taxonomic order, Madreporaria, of the species Montipora...” You get the picture, no permit, no collection. Period. In general, the Hawaiian collecting regulations go like this:

Stony Coral and Live Rocks It is unlawful to intentionally take, break or damage, with crowbar, chisel, or any other implement, any live stony coral from the waters of the State of Hawaii, including any live reef or mushroom coral. It is unlawful to sell or offer for sale any stony coral of the following species: Montipora verrucosa, Fungia Scutaria, Pocillopora damicornis, Pocillopora meandrina, Posillopora eydouxi, Porites compressa, Porites lobata, and Turbastraea coccinea.

Pink and Gold Corals It is unlawful to take, destroy, possess, or sell any pink or gold corals taken from the waters of the State of Hawaii.

Exceptions: (Makapuu Bed, Oahu only) With a permit, to take for domestic or commercial purposes, provided that a two-year quota of 4,400 pounds may be harvested by all permittees, and all harvesters make every effort to collect only mature colonies 10 inches or larger in height with non-destructive and selective methods. This harvesting may be suspended at any time.

Limu (ogo) (a green “sea weed”) It is prohibited to take with the holdfast, the part attaching to a rock or other surface. To take when covered with reproductive nodes or bumps.

Bag Limits for Limu One pound per person per day for home consumption. Ten pounds per day per marine licensee for commercial purposes. No commercial taking on Maui.

Scientific, Educational or Propagation Purposes Any person with a bona fide scientific, educational, or propagation purpose may apply in writing to obtain a Scientific Collecting Permit to legally take certain aquatic life, use certain gear, and gain entrance into certain areas otherwise prohibited.

With permit in hand, I proceeded to plan the collection activity. I knew that my free time on Oahu would be limited, so I wasn’t too ambitious in what I sought. First, it would have to be something that I could get skin diving by myself or from the shore (so I packed only mask/snorkel, fins, and boots). Second, I would have to carry everything on the plane, so collecting had to be done the same day that the flight left. I therefore scheduled a flight leaving around 4 PM, arriving Atlanta the following morning (about 8 hours later when crossing time zones). I packed a small backpack with four half gallon watertight wide-mouth containers, a net bag, several gallon ziplock bags, and my 3-volt battery-operated air pump.

In the days leading up to the collection day and my final departure, I scoped out what might be found in the waters around Oahu. To see the best of what could be collected from within 100 meters of the shoreline, I got up very early and went to the public beach access point conveniently next to the Waikiki Marine Life Conservation District. This was just down from the Hawaii Aquarium and right next to the Natatorium. Not only was there public beach access, but there was parking! I figured that a Marine Life Conservation District (MLCD) would have undisturbed marine life and that I could plan what species to look for prior to going to an unrestricted area.

A great little booklet entitled, “Marine Life Conservation Districts” which I got from the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Aquatic Resources had color aerial photographs of each of several of the Oahu MLCDs so I could see where the shallow-water wave action, channels, and reefs were. The Waikiki MLCD was included in this booklet.

About an hour after sun-up and long before the day’s meetings, I was down at the beach with mask, fins, and snorkel. It was a great time because the tourists were still in bed, and only the local kayakers and joggers were out.

The Pacific is cold compared to the tepid waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The bottom along the shore dropped off slowly at the Waikiki MLCD from about 60 cm deep within several meters of the shore, to only about two to three meters at a distance of 50 meters from the shore. Small dead banding reefs and dead coral heads punctuated the slow drop off.

I was not too surprised at the dead reef. Two years earlier during a similar set of meetings, I went to the Hanauma Bay MLCD to skin dive. Within 100 meters of the shore all of the coral is not only dead, but it is polished smooth on top by the soles of tourists’ feet. Conservationists walk the shore handing out leaflets to the tourists begging them not to stand up on the coral when swimming at Hanauma Bay, but with little effect. There were easily 2,000 tourists along the approximately eighth mile of beach lining the edge of the sunken volcanic crater which forms Hanauma Bay. Most were Japanese, and there was a very large contingent of young (approximately 15 year-old) Japanese girls each with complete wet suites and thousands of dollars in the newest dive gear, paddling around (no doubt uncertified divers) in two meters of water! I vowed never to return to Hanauma Bay unless it was on a dive to the middle where it is too deep for Japanese girls and coral stomping tourists.

So when I saw more dead coral at Waikiki, I wasn’t too surprised, but it wasn’t like swimming out to a Hawaiian version of the John Pennekamp Coral Reef as I’d hoped. The bottom was overgrown with sea lettuce and macro algae. There was an occasional piece of hard coral. Huge, two foot long holothuridians (sea cucumbers) were to be seen along with occasional long spined black urchins. There were many fish, including Achilles Tangs, the Hawaiian version of Sergeant Majors, and puffers. A nice cold swim, but disappointing in terms of seeing the encrusting soft corals, snails, hermit crabs, and sand stirrers that I sought.

Meanwhile, in the evenings, I would go out along the artificial jetty adjacent to my Honolulu hotel to collect snails. These, I kept in the hotel room along with various immature Hawaiian Feather Dusters that I found growing in the sand of a large tide pool near the hotel.

Finally, the day of my return came and the meetings had concluded. I drove up the eastern coast of the island of Oahu in search of a reef close enough to swim to from shore. I would be snorkeling alone, so I did not want to stray far from shore or shallow water. The Tiger sharks which are a problem in the islands tend to frequent the reefs, but I figured that I would be less likely to encounter one in the shallows on the inside of the reef. Another concern was rip tides and wave action. Oahu has some significant wave action on the north and west sides, so I decided to stick to the east side where there were some sheltered bays.

As I inspected the various points where I could put in, I was continually frustrated by the fact that the depth seemed too shallow and there were no apparent reefs close in.

I soon determined that the only reasonable collecting would be done on the barrier reefs perhaps a half mile or more from the shore, so I decided to go to Kualoa Park (see Figure 2) which had a large island dubbed "Chinaman’s Hat" because of its shape, adjacent to the shore. Perhaps an intermediate reef could be found between the park and the island.

It was late morning when I arrived. There were about three groups of campers who had spent the night and were just breaking camp. I gathered my plastic watertight wide-mouth containers and put them in the net bag along with my ziplock bags. The water depth dropped to about one to two meters and stayed that way for as far as I ventured from shore. The entire area was a coral rubble bed comprised of chunks of live rock and broken branches. The bottom was covered with coral sand and was white, but if any object was picked up and shaken, the sand fell away to reveal terrifically colored coralline algae displays. Many macro algae clung to the reef rubble. Some very fleshy gorgonian-like plants/animals swayed in the surge. Unlike the stiffer Atlantic gorgonians which are covered with tiny polyps, these creatures appeared to have a mucous coating and no polyps. There were not many fish in this area (probably good, because there would not be many sharks either!). The surge was rather strong making it difficult to stay on an object once it was found. There was also a current running parallel to the shoreline.

The most interesting places were the one meter coral rocks with large interstitial holes in which life could hide from the surge. I used my diver’s knife as an anchor on the rock while I collected specimens with the other hand. Once I had something, the knife went back into the sheath on my leg while I wrestled to get a collection container open to accept the new find. All the while, the surge was pushing me away from the particular collection point.

I kept a small amount of air in the collection containers to keep them just positively buoyant in case I dropped one. This would also let me find the net bag holding the collection containers were it to get away from me. In some cases, I put specimens in the ziplock bags to keep them separate from other specimens. Some items were very delicate. For example, there were some beautiful purple sea slugs (actually more like giant planaria two and one half centimeters long) that had parallel orange stripes going the length of their bodies. These later became a sacrifice to the circulation pump god when they insisted on taking the water slide from the show tank to the basement sump (and beyond). I fished them out of the sump several times and then one day they were gone.

After my collecting was done (about two hours in the water), it was time to take Hawaii’s Interstate Route 3 back to Honolulu and prepare to sit in a fetal position for eight hours on the board that Delta calls a seat. (By the way, Hawaii DOES have interstate highways. They don’t just drop off into the ocean and reappear in California, but they are designated "interstates" so the State of Hawaii can qualify for Federal interstate highway dollars).

Back at the hotel I segregated the marine specimens into various containers, did a water change with fresh ocean water, and sealed the containers. They were then organized into my small backpack where they stayed until about an hour into the flight home. I opened one half gallon container at a time and used the battery-operated air pump to oxygenate the water for an hour each. A little girl several seats back on the other side of the isle wanted to know what was in the bubbling containers, and I passed back the message that I was transporting human brains for transplantation upon our arrival (she left me alone for the rest of the flight).

Upon arriving back in Atlanta, I immediately put the specimens in the sump for later distribution into the main show tank. It was then that I was able to discover a lot of the pleasant little freeloaders like clear shrimp, worms, tiny snails and the ubiquitous glass anemones that are the bane of the aquarist.

Florida

Collecting in the Florida Keys was much easier in every respect. First, one need only obtain a Florida fishing license to be able to collect from non-protected waters in Florida. Second, I had more time set aside for collection and I was in control of the transportation.

I had to go to Walt Disney World’s EPCOT Center to run the 1997 International Aerial Robotics Competition on July 14, 1997. Since I was already in central Florida with the family, we decided to drive on down to the Keys (about six hours further south) and spend a few days hunting for marine life. I have been diving in the Gulf of Mexico from Panama City, to the Yukatan, in the Sea of Cortez, and in the Pacific, but (excluding fresh water dives), the easiest and most abundant waters I’ve had the pleasure to dive in are found at the John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park adjacent to Key Largo, Florida. So I knew what to expect.

I also knew that I didn’t want to be caught anywhere near Pennekamp while collecting or I would spend the rest of my life in Florida’s jail for tourists, so we went further down to Marathon Key.

Marathon is a good base of operation in that it has all amenities including large grocery stores, a hospital, and plenty of places to stay. We chose the Key Lime Resort which is on a peninsula on the protected side of Marathon Key (NOTE: The Key Lime Resort itself no longer exists, as it has since been torn down to make room for a new development).

Florida collecting regulations can be summarized as follows:

Bag Limit: 20 invertebrates per person per day. No more than six octocoral colonies per person per day. Plants: One gallon per person per day. It is unlawful to harvest or possess Longspine Urchin, Hard and Fire Corals, Sea Fans, Florida Queen Conch, and Bahama Starfish. Harvest of live rock in State waters is prohibited. Because local regulations governing the taking of saltwater products may exist, you should contact the Florida Marine Patrol (FMP) Field Office nearest the location where you will be engaging in these collecting activities.

You Do Not Need a License if You are:

A Florida resident fishing (collecting) from land or a

structure fixed to the land

A Florida resident fishing (collecting) from land or a

structure fixed to the land

a pier, bridge, dock, floating dock, jetty, or

similar structure

a pier, bridge, dock, floating dock, jetty, or

similar structure

but not from a boat.

but not from a boat.

A Florida resident who is 65 years old or older.

A Florida resident who is 65 years old or older.

A Florida resident who is a member of the U.S. Armed

Forces who is not stationed in this state, while on leave for 30 days or

less, upon submission of orders. This does not include family

members.

A Florida resident who is a member of the U.S. Armed

Forces who is not stationed in this state, while on leave for 30 days or

less, upon submission of orders. This does not include family

members.

Under 16 years of age.

Under 16 years of age.

Fishing from a boat that has a valid recreational vessel

saltwater fishing (collecting) license.

Fishing from a boat that has a valid recreational vessel

saltwater fishing (collecting) license.

A nonresident fishing (collecting) from a pier that has a valid

pier saltwater fishing license.

A nonresident fishing (collecting) from a pier that has a valid

pier saltwater fishing license.

A holder of a valid commercial saltwater products license -

other than the owner, operator, or custodian of a vessel for which a

saltwater fishing (collecting) license

is required. (Only one person fishing (collecting) under a vessel

saltwater products license may claim the exemption at any time).

A holder of a valid commercial saltwater products license -

other than the owner, operator, or custodian of a vessel for which a

saltwater fishing (collecting) license

is required. (Only one person fishing (collecting) under a vessel

saltwater products license may claim the exemption at any time).

(Note you are considered a Florida resident if you reside in the state for six continuous months prior to the issuance of a license and who has an intent to continue to reside in Florida and claim Florida as their primary residence).

Nonresident Licenses cost $5.00 for a three-day license, $15.00 for a seven-day license, and $30.00 for a one-year license. Up to two additional dollars may be assessed as local taxes. These licenses can be purchased from the Tax Collectors office or bait-and-tackle shops acting as their agents.

Florida requires that each nonresident adult have a valid Florida fishing license before engaging in collection activities, but note that nonresident kids under 16 years of age can collect without a license. Well, I had both of my pre-teen kids with me, so as a team we could collect 20 of each species of invertebrate per person per day per person-- that is 60 Astrea snails per day times seven days (for a seven-day license), or 420 snails. At Atlanta aquarium store prices of $2.50 per snail (best price), we could harvest $1,050 worth of snails alone! That would certainly offset the $17.00 I paid for a fishing license, or so the logic went.

We didn’t need 420 of anything, but it was nice to know that we didn’t have to worry about collecting too much. Our plan was to survey the area carefully select what we wanted to bring back to Atlanta.

I had constructed two special transport containers from salt buckets.

These buckets have water tight tops to prevent sloshing water from

getting in the car during the trip back, but I had designed a special port

in the top to allow air to be circulated into the bucket and back out

without the possibility of water getting blown out with the exhaust air.

These buckets were used with a dual output 110 VAC, 60 Hz air pump while in room at the Key Lime Resort to keep things collected alive. The bucket lids were left off or only loosely attached while in the room to allow observation and convenient twice-per-day water changes since no filtration was being used. This same pump was used in the car to provide air and water circulation to the buckets. An inverter ran the pump from the car’s 12 VDC accessory plug.

The buckets stayed packed in the car during the ensuing layover on the trip back to Atlanta. So the marine life endured 26 hours in the dark in these transport containers with 100 percent survival rate.

The collection procedure involved both wading and swimming. Unlike Hawaii, there was abundant marine life that could be picked up in knee-deep water during low tide at Marathon. Red-legged hermit crabs were present by the hundreds. They usually congregated in and around tide pools. Astrea snails, though less abundant than hermit crabs, could be harvested in a similar way by walking along and inspecting rocks. Typically, the Astreas are found together. A rock that has one will usually have several on it.

Everywhere on the bottom macro algae, plants, and zoanthids known as "sea mat" can be harvested. Sea mat is very nice for filling holes between rocks in the aquarium reef. I paid $19 for some Indonesian sea mat in the Atlanta area. It is a drab green compared to the sea mat found at Marathon which has a vibrant yellow center under actinic lighting. Not only that, but I could have collected enough to carpet the floor of my house!

Other beautiful things to collect while on foot were the rock anemones. These very colorful (often multicolored orange, green, brown, and white) anemones get into crevices on massive coral reef rocks and are impossible to dislodge, but if you can find a dredged rock bed, rock anemones can be collected because if they attach to a single small rock amid many, they can be removed. One nice thing about the rock anemones is that they seem to stay put once they get a foothold in a crevice, so they don’t wander in the aquarium like other anemones.

During July, much of the sea life found around the Marathon shallows is under rocks trying to stay cool. Flipping over human debris like cinder blocks reveals a cornucopia of specimens. I collected several Terrebellid worms that have long white tentacles. They hide inside my aquarium reef and send out long (up to a third of a meter) filaments which extend along the bottom and over the rocks seeking detritus.

On man-made reefs and wooden piers one finds many colorful feather duster worms. The principal colors are purple, brown, and green. Also in these areas many plants and macro algae can be harvested.

The waters around the Key Lime Resort peninsula are from one to four meters (as far as we swam), but they are laced with dredged channels. This allows some large fish to be attracted to the area. A one meter long nurse shark was observed coming from one of these channels as were many large Parrot fish. Small to medium sized Barracuda were everywhere.

On one day, I was snorkeling and found a pile of bricks– the kind with holes in the middle. I flipped over one and there was a small unknown variety of orange fish in it. The fish would not leave the brick, so he earned an all-expenses-paid trip back to Atlanta. After quarantine in malachite green, he was released into the show tank where he promptly disappeared into the reef, probably never to be seen again.

Under some WWII vintage electronics chassis found in about two meters of water, I was able to collect some large Terrebellid worms. Under rocks I found a red brittle star, a red/black urchin, and various serpent stars, all of which were collected. A few small conch mollusks were gathered along with a limpet or two to increase my tank’s biodiversity. I passed over all of the Condylactis anemones as most were too big and too mobile.

A purple gorgonian of just the right size was collected and it surprisingly kept its polyps open the entire time it was in the buckets and upon arrival in the show tank. A similar one purchased from a dealer in the Tennessee area, though healthy, took several weeks before it would open its polyps once introduced into the same tank.

The prize collection of the trip was a beautiful corky sea finger. This is a thick fleshy purple gorgonian with very long polyps. I found it on the second day of snorkeling and marked its location on the bottom with a large piece of metal that looked like an airplane wing aileron that I found nearby. I also triangulated its position from shore features so I could find it again.

I did not want to harvest it until the last day of our trip in order to minimize the stress it encountered, and also because it would take up a large portion of the bucket area.

Each day I went back to check on it. Finally, the evening before we packed up to go, I relocated it and cut it from the base rock with my diver’s knife. I used my half-gallon containers for most collecting, but I used my clear plastic two-gallon water change jug to hold the corky sea finger due to its size. Upon introduction into the tank in Atlanta, I used a gel cyanoacrylate to affix the sea finger to a flat rock where it seems to be quite happy, exhibiting good polyp extension.

Clearly, both the Hawaii and Marathon collection trips would have been much more productive had I gone out to the deeper water reefs, but I have demonstrated that near the shore without using scuba, many desirable species can be gathered, and the entire family can participate (though that is not always a benefit-- my 12 year old son was just getting used to mask, fins, and a snorkel on the Marathon trip. He was like a Pilot Fish. Wherever I was, he was there. Sometimes he was more like a Remora however. He was under me when I was homing in on the ideal specimen. I’d flip over a rock and there was the most beautiful star fish, but as I would reach for it all of a sudden there would be flippers in my face and a cloud of silt. Gracefulness and conservation of motion underwater is something still to be learned. It was very gratifying to see the excitement of both boys as they discovered a new oddity such as a school of squid, or real dangers such as the dreaded mantis shrimp).

In summary, here are some pointers for collecting your own marine specimens.

- Carry suitable wide-mouth containers. They should have lids that

unscrew in less than one turn. Keep some air in the lid so they are just slightly

buoyant if you are skin diving, or allow them to completely fill if scuba diving.

- Keep your collection bottles in a net bag where you can see them and get

to a particular one easily.

- Ziplock bags are handy for segregation of specimens.

- Always have a dive knife. Use it to turn things over (not your hand!).

There is a lot of invisible fishing line near the shore that can entangle you and

keep you under. Be able to cut yourself free.

- Wear gloves. White cotton gloves are sufficient to keep the stinging

cells on tiny unseen anemones and other sea creatures from making your

fingers numb after handling items on the bottom. Coral is also quite abrasive

and the gloves will protect your hands.

- Don’t touch anything with which you are not familiar. Don’t put

hands or fingers in holes.

- Keep incompatible species segregated. They may be able to coexist

just fine in your show tank, but may not get

along well when confined to the same collection container or bucket. - Keep aerated specimen containers in a cool place out of the sun.

Leave things in the ocean until the time is

right to collect them. The less time in transit and unstable conditions, the better.

- Do water changes at least daily (more often if possible). Take

extra clear sea water when beginning a long car trip back to your home base so

that you can still do daily water changes along the way.

- Get things into a quarantine tank as soon as possible after arriving.

Schedule your return trip to allow this.

- Don’t get so wrapped up in what you are collecting that you lose

track of your situation. Where is your buddy? Is there a squall approaching you at

30 kts? Is there lightning in the area? Are you having trouble seeing the

worm that you are trying to collect under that rock due to the billows of

red obscurring the water shortly after you felt a gnawing pain in your thigh?

- Stay out of the sun as much as possible, and wear cloths or a wet suit

to cover exposed skin if collecting during mid day when the lighting is best.

- Get your permits well in advance of your trip unless permits are

easily obtained such as those in Florida.

- Know the laws and be able to identify species (at least better

than the local enforcement officer). Consequences can be stiff in

Hawaii most violations are subject to a fine of up to $500 and/or 30 days in

jail, plus up to $100 per specimen taken illegally (first conviction). One

half of the fine imposed and collected in cases where the defendant has

been convicted for a violation, is paid to the person giving the

information leading to the arrest of the convicted aquarium felon, so there is

incentive for locals to turn you in if you appear to be exceeding your Limu limit!

- The key to a successful collection trip is planning beforehand.

|

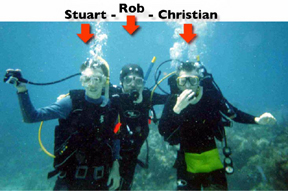

All the members of the Michelson family are certified divers and enjoy the excitement of collecting just the right specimens for the aquarium. |

Return to Michelson Aquarium.